Getting Out From Behind the Power Curve

John Gadzinski knows a little something about power curves.

“You can get into a position in an airplane where no matter how much thrust you get from the engine you can’t go any faster or any higher,” said John, a pilot for the last 38 years, first for the U.S. Navy and now for Southwest Airlines.

It’s called being behind the power curve.

“No matter how hard you work you won’t go any farther,” John said. “The objective of the pilot is to never get behind the power curve.”

The same is true for human beings, John will tell you.

“Some people find themselves behind the power curve of life,” John said. “They face problems they just can’t get ahead of, no matter how hard they work and how much they try.”

That’s why it’s important to give back. That’s why it’s important to support the community.

“That’s why it’s important to do what we can for Habitat for Humanity,” John said.

And that’s just what John has done.

John recently sold a house and nearly a full acre of land in Williamsburg, Virginia to Habitat for Humanity Peninsula and Greater Williamsburg for far below its value as a way to give others in life a hand up to get out from behind the power curve.

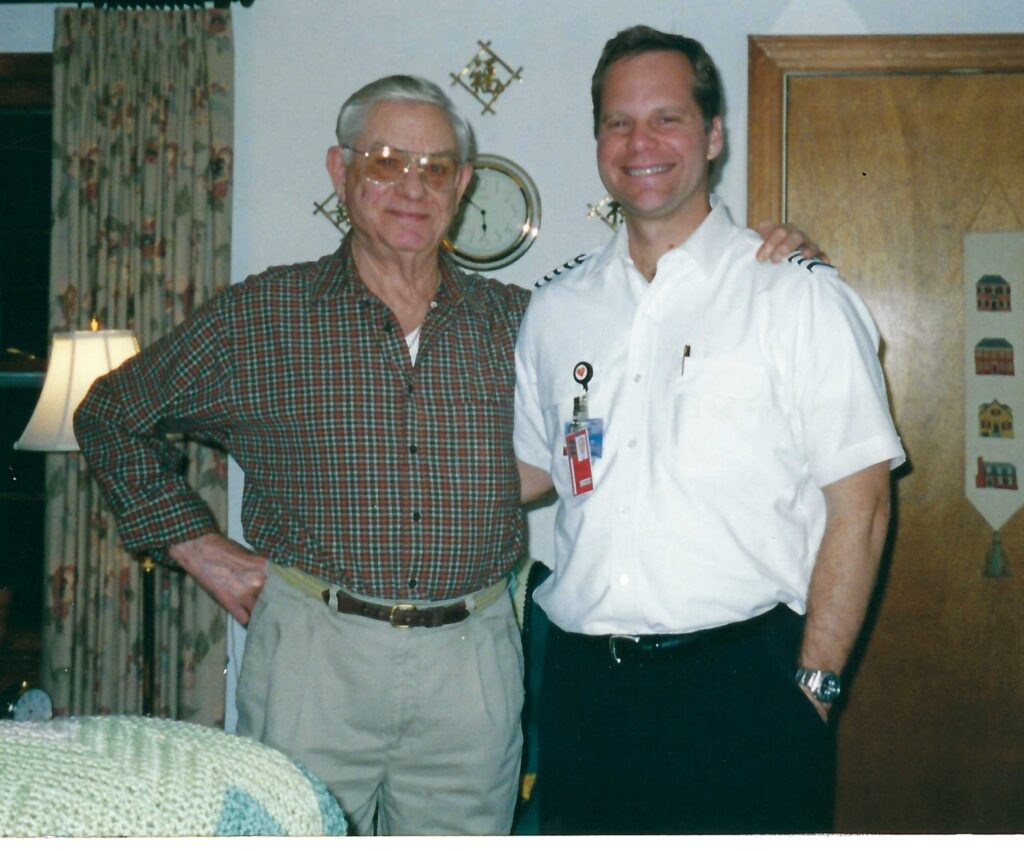

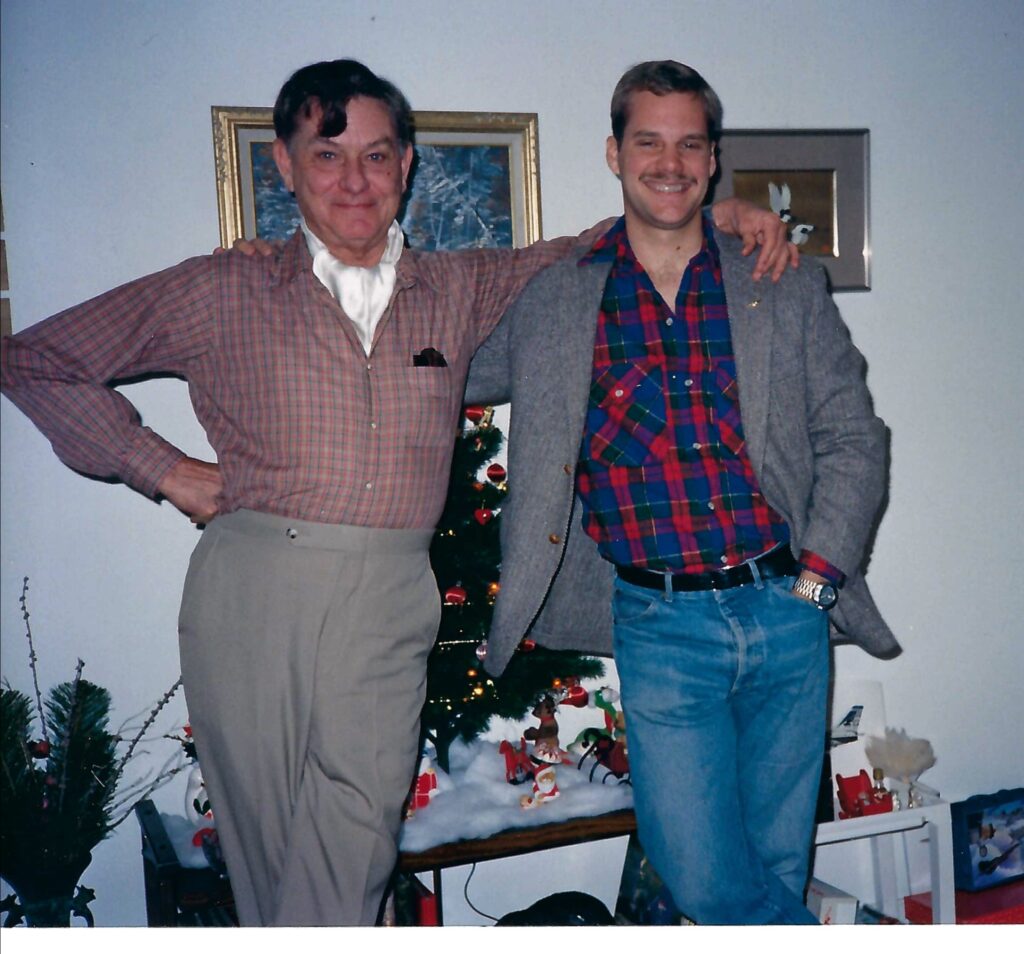

The house, built in the 1960s, was made into a home by John’s mentor and lifelong friend, Prentice A. Layton, Jr., whom he lovingly called Tex.

Tex and his wife never had any children and when they passed away left John to be the executor of their estate.

“We were trying to figure out what to do with their estate, which the house was part of,” John said. “It was kind of a rectangular brick starter home and was going to take some work put on the market to sell it.”

One of the things John and the other members of the trust who were going to get disbursements looked at was finding a way to get it into the hands of Habitat for Humanity.

The house was assessed at $200,000, but, John said, they sold it to Habitat for their standard house rate, which equaled a steep discount, and far less than the trust could have gotten on the open market.

“We could have fixed it up, or sold it to someone who was just going to flip the house to make more money, but there is more to life than money,” John said. “It was important for me and it was important for all of us part of the estate to try and give back. We all decided that we could do something good for the community with this home. That we could actually make a difference.”

John said he lives by the belief that you get one shot in life “and you should do something decent and worthwhile and not always be thinking about money.”

“When I was flying combat missions in the F-14, I remember flying over Iraq and thinking that the only reason I was in the F-14 and not on the ground was because of where and how I was born,” John said. “None of us should be arrogant about success. All of us should try and do some good in the world. We all benefit by helping our fellow people out.”

Supporting Habitat, John said, “was going to be a catalyst to help creating generational wealth for others.”

Tex would have wanted that.

John met Tex when he was 19-years-old and working as a musician at Busch Gardens on breaks from being a student at Boston University.

“I went to Williamsburg Jamestown Airport with my Busch Gardens money to take flying lessons and was told early on that I needed to talk to Tex,” John said.

“He was as unique a character as there ever was,” John said.

Tex entered the Merchant Marines in 1942 and served in World War II until 1945. That alone meant he was a survivor. Merchant Marines suffered the highest casualty rates of any service during the war, although it was not until 1977 that the U.S. officially recognized them as veterans.

According to his obituary, which John wrote, Tex was 42 when he jumped into the debris filled waters and 100 mph winds in Naha Japan after several mooring ropes from a ship had snapped. His actions saved the ship and in 1967 the U.S. Army awarded him its highest civilian award, the Decoration for Exceptional Civilian Service.

Chances are locals came in contact with Tex, too, as he was a captain on the Jamestown Ferry after retiring from his sea going career that included serving with NOAA, the Coast Guard, as a civilian sailor for the Army and as a harbor pilot.

“I became his de facto son for a long time,” John said. “I would come back from a tour or a cruise or combat and Tex was one of the few people I could talk to about being in a world where things were dangerous. He would make martinis. We would talk. We were very close.”

Tex, John said, would have been proud to have his home do some good as part of his legacy.

“He was very old school and very proud,” John said. “He came from kind of a broken home and had been through a lot.”

Somehow Tex got out from behind the power curve.

“I am one-thousand-percent confident he would have approved of the good we did with his estate.”

Interested in donating land or property to Habitat for Humanity Peninsula and Greater Williamsburg? All land and property donations are tax deductible, and some are eligible for tax credits. Donors with land or property in Hampton, Williamsburg, James City County, Newport News, Poquoson, York County, Charles City County or New Kent County are encouraged to contact info@habitatpgw.org or (757) 596-5553.

We’re closing out our Yorktown ReStore 2nd

We’re closing out our Yorktown ReStore 2nd

FLASH SALE WEEKEND AT @restorepgw

FLASH SALE WEEKEND AT @restorepgw